- President Ruto orders police to shoot looters in the leg, not kill them.

- The remarks follow violent anti-Finance Bill protests that left over 30 people dead.

- Ruto accuses unnamed leaders of funding chaos and sabotage.

- Civil society groups condemn the directive as a green light for police brutality.

- The government insists vandalism, looting, and attacks on stations are acts of terrorism.

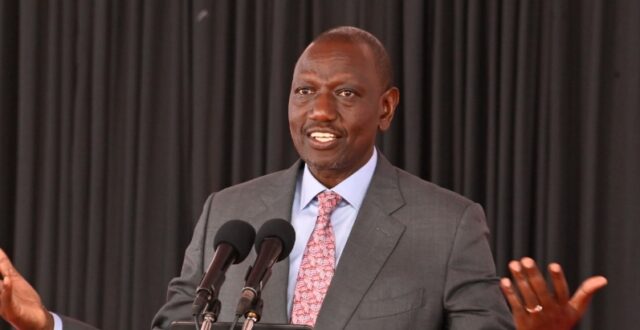

President William Ruto has triggered fierce national debate after instructing police to shoot protesters caught vandalising or looting during demonstrations, but not to kill them.

Speaking on Wednesday at the unveiling of a police housing project in Kilimani, Ruto said the state will no longer tolerate destruction of private or public property.

“If someone burns another person’s business or property, shoot them in the leg. Let them be treated in hospital on their way to court,” said Ruto.

“We will not allow criminals to hide behind protests.”

The president made it clear that his directive aims to stop what he termed “terror-like tactics” by protestors, especially those attacking police stations, public buildings, and courts.

The remarks come days after the June 25 protests turned deadly across the country, with 31 people reportedly killed and over 100 injured, according to the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights.

The protests, driven by widespread anger over the controversial Finance Bill, saw violence erupt in at least 15 counties. Some demonstrators torched five police stations and damaged government buildings in acts the state has branded “domestic terrorism.”

President Ruto also accused certain unnamed political figures of paying young people to destroy the demonstrations.

“These are not ordinary citizens protesting. These are well-funded criminals sent by politicians. We are tracking you,” he warned.

Interior CS Kipchumba Murkomen had earlier echoed the hardline stance, saying police should not hesitate to shoot anyone trying to storm a police station.

“Firearms are not doughnuts!” Murkomen declared.

Civil society groups, opposition leaders, and international observers have condemned the president’s shoot-to-disable directive, calling it a violation of constitutional rights and a license for excessive police force.

Rights activists argue that instead of using violence, the government should engage in dialogue and reforms to address citizens’ grievances.

“Ruto is normalising state brutality,” said a joint statement by several human rights organisations.

With public pressure rising over the economic crisis and police brutality, Ruto’s administration is walking a fine line between maintaining order and upholding civil liberties.

The coming weeks will test whether the government can rebuild trust, or whether its hardline posture will deepen the standoff with a restless, increasingly vocal citizenry.